BLAKE VOGT: All right. Welcome Jim Steinmeyer to “Inventing Magic,” Episode 5. Thanks for being here. I appreciate you doing this. This whole thing exists because of you.

JIM STEINMEYER: Not really, but we’re responsible for putting it in Genii. We talked about the possibility of doing something, and you suggested this. As I recall, the first thing I said to you was that we don’t subsidize mental health bills. But you figured out a way that works.

BV: It’s all a ruse to have an excuse to finally get to jam with you creatively. So the day has arrived. The jig is up. You are in a room that looks like it is filled with books. Is this your office?

JS: Yes, it’s an office. It’s got books around different subjects, and I’ve got space to work and space to draw. It’s one of those rooms where you can make a mess and then get up and walk away.

BV: Great. You said you had ideas that hadn’t necessarily been finished in your mind.

JS: I would say that’s the story of my life. I worked with a guy at Disney who was a really fantastic artist, Rolly Crump, who said that he had been buying books all his life. And he said, “When I retire, I’ll read the books.” And I do feel like my goal is to get to a point where I can go back through ideas and fix them, finally, [and] totally finish them.

BV: Having a body of unfinished ideas, or idea starters, is very helpful. I learned that early on. I got to work with Danny Garcia and he would spout endless amounts of ideas that different clients necessarily wouldn’t bite [on]. But, I’d remember them, and we’d write them down for the next client or the next project.

JS: But that’s part [of it], processing that stuff and keeping track of it. Over time your recollection of it [changes] and you’ve now dropped another little bit of information into it. So keeping track of that stuff is super important.

BV: Well, this is really fun. Whatever we talk about today will go in Genii.

JS: I take a lot of time with magic. That’s my one little caveat. I realized a few years ago, I actually slowed down at the end of an idea, because I worry that racing over the finish line is when you make mistakes. When you almost think it’s done, that’s when you’re making the wrong judgments. And so very often I’ll be very close to something, and I’ll close the notebook and I’ll leave it, if I can. Because percolating on it is how you get to the fine points.

BV: With some of the things that you’ve worked on being so big, are there smaller versions of them that you work on to work out the kinks?

JS: I have little cardboard models on my shelf. And that’s incredibly helpful [for] showing it to somebody, because then they see the limitations of it.

BV: I was also wondering, how many things you’ve worked on, or principles with bigger props would necessarily translate to, [for example,] a card box or to something that would fit in your pocket?

JS: It doesn’t often. But I do think a strong premise will…. You know, there are really crummy tricks in magic, but they are beloved. We know from past experience why a trick might be good. And yet, we also know, after years of experience, what’s wrong with it.

Like the Six Card Repeat, which is just completely pointless. And in fact, the guy who invented it, Tommy Tucker, I knew him, and Tommy said that he invented it only to demonstrate the false count to magicians. Everyone thought it was so funny, so they started doing it. It was really to demonstrate that Glide False Count that he did.

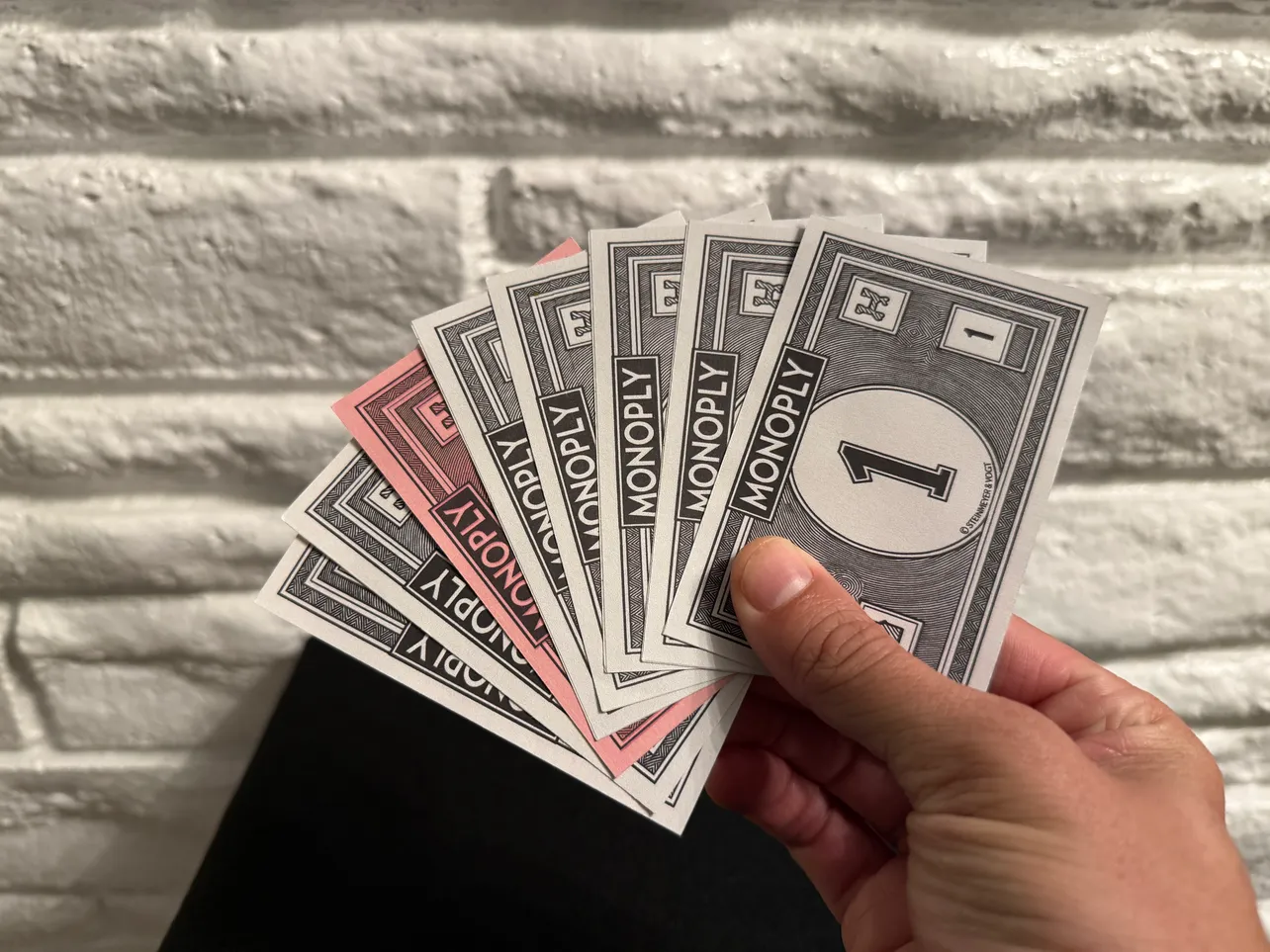

So there’s a trick that needs to be fixed. It feels like it’s a short change trick somehow, probably should be done with bills. But the mechanical versions of it that have been done with bills are just awful. It needs to feel like a sleight-of-hand piece. It needs to have a plot that feels like it’s short change.

BV: Chris Kenner gave me great advice one time. He said, “If you are ever stuck creatively, pick a trick that you hate and write down all the reasons why you hate it, and then fix those reasons, and then you might end up with a new trick.” What is the thing about the Six Card Repeat?

JS: I would just say there are tricks and situations that make the person funny when the person’s not funny, right? And the Six Card Repeat is like that.

BV: I’ve seen it done with bills before. I know I have, but has anyone ever done it with—bad version—a $100 bill, and then, as you count it, it turns into two $50s?

JS It super needs a finish. I mean, the goal of it would be that in all of the changes with the $1s, that suddenly what you got out of it was the $1s back again. So you’ve ended up with all the bills that actually meant anything.

BV: It could also be nice as a bonus, and we’re talking about a trick that could also potentially need a week to figure out the math….

JS: Welcome to my world. I knew I was going to screw this up. Everything I do ends with, “Yeah, that might work. Let’s think about this for the next week.”

The following routine was created in one hour. Both creators agree that it could take weeks to work through all the necessary details to make this effect feel truly smooth and mathematically accurate.

And yet, they’ve created a fun and frenetic shortchange routine with fuzzy logic that is quite appropriate to the premise. Unlike many routines of this nature, nothing is added or taken away. We’ve included a rough script to give you a sense of the routine’s beats.

While there is a great deal of room for experimentation and audience management, we’ll assume that you are doing all of the counting and bill handling on behalf of the spectator.