Genii was already 59 years old when I first discovered it. I was five. I folded my child-sized frame over the side of a weathered, black steamer trunk filled with treasures: disintegrating instruction sheets and dogeared magic shop catalogs rubber banded into piles. Silk handkerchiefs desiccated into their folded shapes, hidden at the bottom of a rusted change bag. A scuffed milk pitcher wrapped in long-yellowed newspaper. And a small stack, in pristine condition, of issues of a singular magic magazine: Genii.

My father was born in Brooklyn in 1943. He grew up taking his pocket change to Flosso’s Magic Shop. He did Hippity Hop Rabbits at local kids’ birthday parties as a teenager, performing on a homemade folding table with his stage name scrawled in glitter glue. He joined a few clubs, he still pays his dues. Magic had long since faded from his life by the time he brought down that trunk from the top shelf of the hallway closet. But he still had all his old stuff, and I was a curious kid. Maybe he had a hunch.

We spent many afternoons messing around with the props, trying to reconstruct effects from his memory. Much of the apparatus was unusable. What had been preserved, though, was story.

We all have a story of how we got hooked. Many profiles have graced these pages following the now-set formula: So-and-so was born in this year, in this place. He got his first magic kit when he was this old. Ta-dah! A magician is born. I’ve heard this structure called either The Resume or The Obituary, reflecting readers’ (and writers’) frustration with the repetitive format.

Although the details vary, most of us can instantly relate to this rote formulation. Some of us were adults, not children, when we first fell into the grip of magic. We got a book instead of a kit. Maybe we saw a local show, or had a punny uncle who pulled quarters, or crawled up to the television set to touch the screen when Max Maven told us to during the bumpers of The World’s Greatest Magic in 1994. Whatever it was, we can usually remember the moment we got hooked.

As a kid, being dropped into the middle of magic’s story made me wonder what had already come and gone outside my frame of reference. My dad’s stash of ‘50s and ‘60s Genii copies was a time capsule to the past. But when I fell into that steamer trunk in the ‘90s, I had no idea magic was trapped in a rut and Genii was in a tailspin.

Technology was, as usual, pushing society to new frontiers. Home video had become a dominant media format. The proliferation of network TV specials had settled magic on screens in a new way. Behind the scenes at Genii, evolving technology meant transitioning from manual cut-and-paste processes to digital operations. And the changing tide of Genii leadership birthed a new era when Richard Kaufman took over in January 1999.

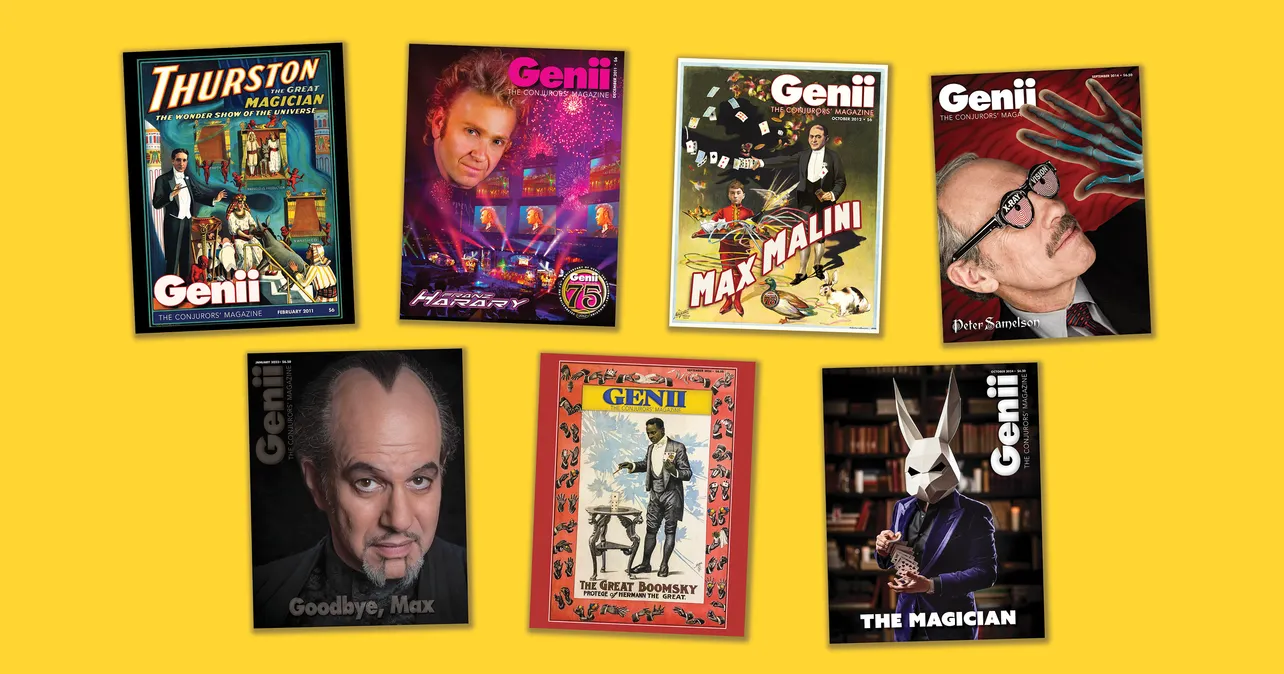

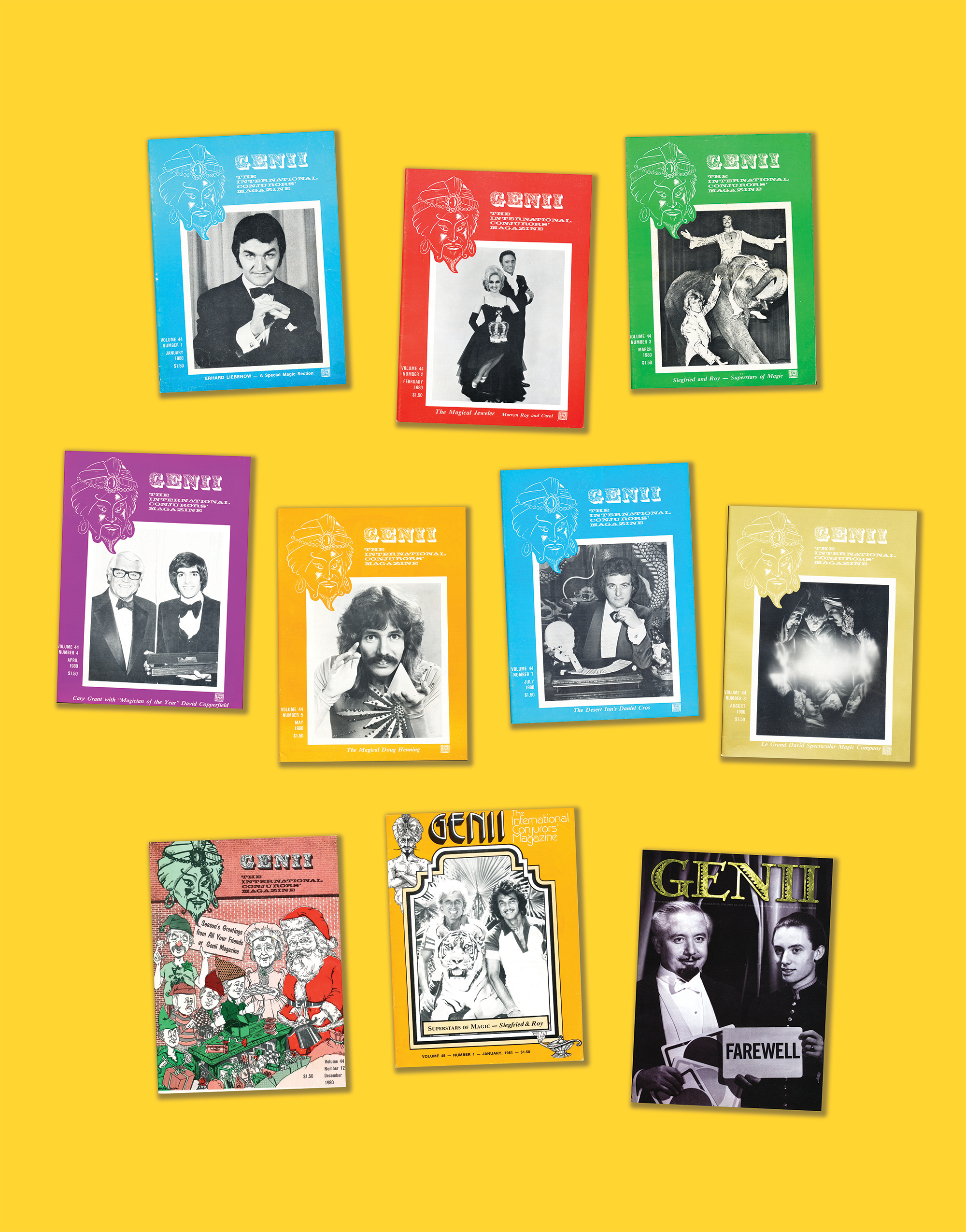

Max Maven documented this changing of the guard and many other magic world shifts in the November-December 2012 double issue commemorating the magazine’s 75th anniversary. It was a revised and expanded version of his 60th-anniversary history published in September 1996. The mammoth piece spans more than 20,000 words spread across 150 pages, decorated with over 400 Genii cover thumbnails and interspersed with 69 tricks from issues past.

It traced the magazine back to the 1930s, when magic clubs in the United States were well-established on the East Coast and in the Midwest. West Coast magicians craved that level of organization. The Diebox, the official magazine of the Pacific Coast Association of Magicians (PCAM), ran from 1933 to 1935. Pacific Coast Magic News took its place until September 1936, when it also shuttered. PCAM decided to fulfill existing subscriptions with Genii, a new magazine from William Larsen Sr. The first issue was 34 pages long. It cost 10 cents—about $2.25 today, adjusted for inflation.

From its earliest days, Genii worked hard to shake its reputation as a West Coast journal. But then it became the unofficial house organ of The Magic Castle thanks to the Larsen connection: The family founded both institutions, in addition to the Academy of Magical Arts, and many generations of Larsens have stewarded them over the years. The California vibe stuck, despite decades of efforts to expand the magazine’s lens by editors William Larsen Sr., Geri, Bill Jr., Irene, Dante, Erika Larsen, and later Richard Kaufman.

In a way, we’re still stuck with this West Coast categorization. Today, Genii and The Magic Castle again share ownership in Randy and Kristy Pitchford. Until now, The Magic Castle has been the only magic theater to receive regular in-depth coverage in the magazine.But in our unofficial and admittedly unscientific reader survey, 38.5% of you said news about The Magic Castle is your least favorite part of Genii. This should not be interpreted as a slight against the “Knights at The Magic Castle” column but rather a reflection of how magic readers’ interests have broadened.

Genii subscribers have always been well-distributed; as far back as 1957, Bill Larsen Jr. wrote that 90% of readers weren’t West Coast residents. But information also moves differently today. Not only are there more thriving hubs of magic spread across the globe, but thanks to globalization and our dear old internet, we’re more connected than we’ve ever been. We take for granted the ability to interact instantaneously across any distance.To meet this modern moment—and to live up to our moniker as an independent magic journal—Genii must present a dynamic and diverse perspective.

Max Maven's 2012 history traced the rise and fall of no fewer than 85 distinct magic publications. The Conjuring Arts Research Center lists over 175 titles in its Ask Alexander database. The Sphinx, which ran from 1902 to 1953, was once seen as “the colossus of the field,” as Max put it. In 1989, Genii replaced it as the world’s longest-running independent magic magazine. ( The Magic Circular, established in 1906, is officially the longest continuously running magic magazine, but is not considered independent due to its official affiliation with The Magic Circle.)

Today, magic periodical publishing is limited. Other than Genii, active general interest titles include the digital-only Vanish, Magicseen in the U.K., and Conundrum, a new project out of Canada. There are club journals: The Society of American Magicians has MUM, the International Brotherhood of Magicians has The Linking Ring, and The Magic Circle has The Magic Circular. Specialist titles include Conjuring Arts Research Center’s Gibecière, the New England Magic Collectors Association’s The Yankee Magic Collector, and Magicol.

Beyond the world of magic, the media industry is fighting for survival. Widespread layoffs, rapidly declining readership, and dramatic corporate shake-ups signal cause for concern. But research shows there is hope yet for media groups willing to adapt; the Newspaper and Magazine Publishers Global Report projects the print media market will grow from $204 billion in 2023 to over $231 billion by 2028.

To ride that wave, media companies of all shapes and sizes are reconsidering their business models. One option is to niche down with an emphasis on aesthetics. Remarking on the resulting resurgence of specialty print titles, Bloomberg has credited longform journalism, high-end art, and strong brand identities with the transformation of magazines into luxury goods.

Art of Play’s loosely magic-related Tangram and art and magic crossover The Neat Review have succeeded here, embracing a design first approach to high-quality and highly specialized print products (with price tags to match). To break through—let alone turn a profit or last—modern magazines are being reimagined as beautiful, thoughtful objects crafted for dedicated audiences.

Another option is to take digital media seriously. Referencing its reorientation around digital media, CEO Roger Lynch declared that Condé Nast, owner of publications including Vogue, GQ, Vanity Fair, and The New Yorker, is “no longer a magazine company.” As publishers seek to offer subscribers increased value and maximize advertising revenue, combining print and digital offers a life raft.

Print is dead, magic is dead, we get it. And so we return to Genii.

Our audience is more digital than ever before, because humanity is more online than ever before. Even the fervent Luddites among us would be hard-pressed to move through daily life without interacting with technology in some way. And the more we do, the more normal it becomes. Expectations around digital experiences are high, especially among younger generations who don’t remember what life was like before the internet. Or Instagram.

Our plans for the new Genii are anchored in digital with a healthy respect for print. As you can already see, we’ve adopted a new aesthetic. Behind the scenes, we are hard at work curating the right combination of online and offline elements to honor the legacy and promise of the Genii brand. There are plenty of surprises in store; that’s all we’ll say for now.

Genii is a trade journal in that it has long served industry members as opposed to the lay public. But if we were publishing a trade magazine for real estate agents or surgeons, it would be a lot easier to distinguish the in-group readership from disinterested outsiders.

An independent magic trade must juggle the interests of professionals, amateurs, and hobbyists. (That’s without even considering magic’s burgeoning fanbase and the untapped audience numbers they represent.) It must dance between many different types of magic and performance spaces. It must fight against the entropy inherent in a subculture. It must constantly question where to draw the boundaries around this niche art form beset by chronic information hoarding. And it must consider how to connect with its audience through the dominant media of the day. Otherwise, things get boring.

In terms of public perception, the 1970s were one of magic’s major peaks. “The art had not reached this level of prominence since the glory days of Hermann and Kellar,” Max wrote of the era. Time and Newsweek covered the magic fever spreading through the public. In Genii, Bill Larsen Jr. reported on the hunt for the next U.S. magic star: “Keep your eye on this lad for great things in years to come” (Doug Henning). “Magic can be proud of these two young men [who have] climbed to the highest rung of the show business ladder” (Siegfried & Roy). In Las Vegas, at least one new casino was opening each year. David Copperfield’s first TV special aired in 1977.

Magic conventions sold more tickets, magic clubs accepted more members. Genii circulation was at an all-time high. There was a lot to be excited about. But the euphoria didn’t last. By the mid-1980s, the public’s passion for magic was waning. In his 1983 column, Larsen Jr. admitted that the magazine had become “too predictable.” Max called the Genii of the ‘80s “musty, even quaint.” He wrote: “The formula that had allowed the magazine to sail through the 1970s had become far too familiar. There was, to be sure, still a large surplus of affection for the magazine, but one certainly would not regard it as hip.”

This is not unlike where we find ourselves today. Following in the Larsens’ footsteps, Richard and Liz Kaufman built a temple to magic in the pages of this periodical. They executed a strong artistic vision and constructed a well-oiled machine that, unlike the Genii they inherited, meant the magazine came out on time. They steered the magazine through another surge of magic fandom, as the 1990s introduced the world to Ricky Jay, Penn & Teller, and David Blaine. But even as magic now hurtles toward what I suspect we will one day remember as another peak of public prominence, Genii has struggled to stay afloat.

In the August 2024 column announcing his retirement, Richard Kaufman wrote that “since 1999, Genii either broke even or lost a little money each year.” He documented the cash infusions and changing ownership that supported the magazine. The fact is that Genii has only been able to survive in its current form thanks to generous financial backing from Randy Pitchford. Keeping his promise to Irene Larsen, Randy kept the magazine from going out of business. But the artificial life support that protected Genii from extinction has also sheltered it from existential pressure to evolve.

This new editorial team is venturing out from that shelter. We are excited to make change and evolve the magazine to reflect a balance of history and innovation, heritage and progress. We have been tasked with reimagining this beloved periodical, reinvigorating a magic brand imbued with nearly a century of history, and building in its name a modern media organization with room for it to grow and thrive for many years to come. But as we work to realize a new era for Genii, we must also seek out long-term financial sustainability.

One think apparent in Max’s heart-filled history is that Genii has always been a labor of love. Contributors, columnists, writers, editors, proofreaders, artists, photographers—countless dedicated individuals have donated their skills to bring Genii to life. Throughout the magazine’s history, few were paid to contribute. Even fewer have called Genii a full-time job, though that’s not to say they didn’t pour their hearts and souls into the work.

When contributors aren’t paid, achieving any semblance of quality is dependent on the generosity of people who really care. The columnists you know and love aren’t writing in this magazine because they have nothing better to do. And while there is certainly prestige in writing for the world’s longest running independent magic magazine, magicians know better than most that prestige doesn’t pay the bills.

For more than nine decades, Genii has been built on the contributions of intelligent, creative, and accomplished magicians eager to steward the art and inspire the community. Fair compensation is a moral standard with which we can all agree. Beyond that, imagine what new heights we will reach when we can compensate contributors for their work. This aspiration adds pressure to our mission to find our footing in a sustainable business model.

So does the fact that it’s difficult to defend criticism when writers are neither being paid nor paying for access. Professional reviewers’ reputations depend on their ability to deliver frank, unbiased opinions, regardless of whether they received a press ticket to a show or an advance copy of a book. True criticism requires honest analysis, and we risk losing that honesty when a non-professional but passionate writer’s only compensation is access.

Modern media production is expensive, and magic magazines aren’t there yet. But Genii has reached a level of maturity that we must respect. Magic’s “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine” system of favors is a symptom of our long legacy as an exclusive boys club.It's a tacit agreement that enshrines existing power dynamics and means it’s all about who you know, under the guise of community friendliness. It’s not that we don’t want to be friendly, but more than that, we want to be fair.

Magicians haven’t always been seduced by the puff piece, and Genii has gotten spicy. Columnists both named and pseudonymous leveled stinging feedback at their peers. There was at least one threat of litigation. There were rivalries and feuds. Many blew over, some blossomed into friendships. In 1939, Larsen Sr. wrote: “In these pages we have, from time to time, lambasted certain people that we figured needed some lambasting.” In 1947, he even renamed his “The Genii Speaks” column “Facing the Facts,” intending to “stop spreading sugar-coated propaganda with a promise to call out shots as we see them.”

Since its inception, Genii has flirted with this desire to trade hobnobbing and rubbing elbows for harsh truths that might push the art form forward. It didn’t always work out. We have been bold, and cowed, and bold again. By the 1960s, Genii had taken on a tone Max described as “benign” and “amiable.” Blunt opinions later re-emerged; Richard was well-known for publishing his even before he took the magazine’s helm.

There has always been some appetite for controversy in Genii, depending largely on who was under fire and who was holding the gun. Surely Genii’s Goldilocks porridge bowl is waiting somewhere out there between lambasting and milquetoast. Maybe finding it and tucking in will help us inch closer to the ideal of “critique as a form of care,” as writer and professor Kemi Adeyemi named it in her essay “On Bad Art(s) Writing.”

Magazines, like magic, must constantly adapt. In the past, Genii editors have attempted to modernize by adding new series, courting fresh voices, and introducing new visual styles. Our editorial team is taking many of those steps again today. But anytime we change the masthead, we run the risk of putting fresh paint on a house in need of renovation. And so I return to our initial question: What is this magazine? Who do we serve? What is our mandate? And how will we know if we succeed?

A monthly magic trade journal once made the far corners of the magic world feel a little closer, but gone are the days of consuming news in print (and paying for it). Popular magic effects now accepted as established classics were first published in Genii—that’s a trend we will continue. Our in-depth profiles will still span pioneers, up-and-comers, best-kept secrets, and full-fledged stars, albeit from new voices and points of view. And as we plow forward, we will never stop looking back to embrace the many lessons tucked away in magic’s rich and textured history.

We will also continue Genii’s long track record of situating magic within its broader cultural context. In the ‘40s, for example, nightclubs had taken over from the vaudeville circuit and magic was moving from top hats and tails to clever talking acts just as the world went to war. Genii introduced a “Magicians in the Service” column and published war-themed routines to ensure we weren’t perceived as out of touch. Take that as proof that we can pull our fingers out of our ears to pay attention to what’s happening in the world around us, to magic’s benefit.

Like the shifting sands of geopolitics, the rapid pace of technological innovation has also influenced the changing face of magic media. The development of new publishing technology led to a veritable magic book boom. Television led to VHS and then to DVD, which opened the door for downloadable video and eventually streaming media. Today we find ourselves awash in social media platforms that represent a cultural ecosystem in their own right. With this climate in mind, our editorial team aspires to build a monthly magic magazine that is curated, relevant, and essential.

In Genii’s first year, Larsen Sr. wrote, “Editorially, there is no use talking about our policies: we have none… Our only allegiance is to magic.” This new team shares that allegiance. The great beauty of having five people work together to make this magazine—with the support of many more—is that we each express that allegiance in distinct ways. We all remember how we first got hooked. The magic bug works through us in mysterious ways. And like you, we all love Genii.

“Genii is truly ‘an independent magazine for magicians,’” Larsen Sr. wrote in 1937. “It's only dictator is whatever conscience its editor may have.” This publication’s editorial conscience is now a collective endeavor in a way it hasn’t been before. That collective should always include you, the reader, and prioritize our audience’s best interests. As for policies, we have some. But as Jim Steinmeyer has been saying since the team’s first meeting, we’re not going to talk about it, we’re just going to do it. We hope you like the magic magazine we make.