Over 400 years ago, the owner of London’s Rose Theatre scrawled down instructions for a card trick between his day-to-day accounts of the establishment. That man was Philip Henslowe, and if you’re a Shakespeare aficionado, his name and his theater may be familiar—his Elizabethan venue hosted some of Shakespeare’s plays, including Titus Andronicus and Henry VI, Part 1.

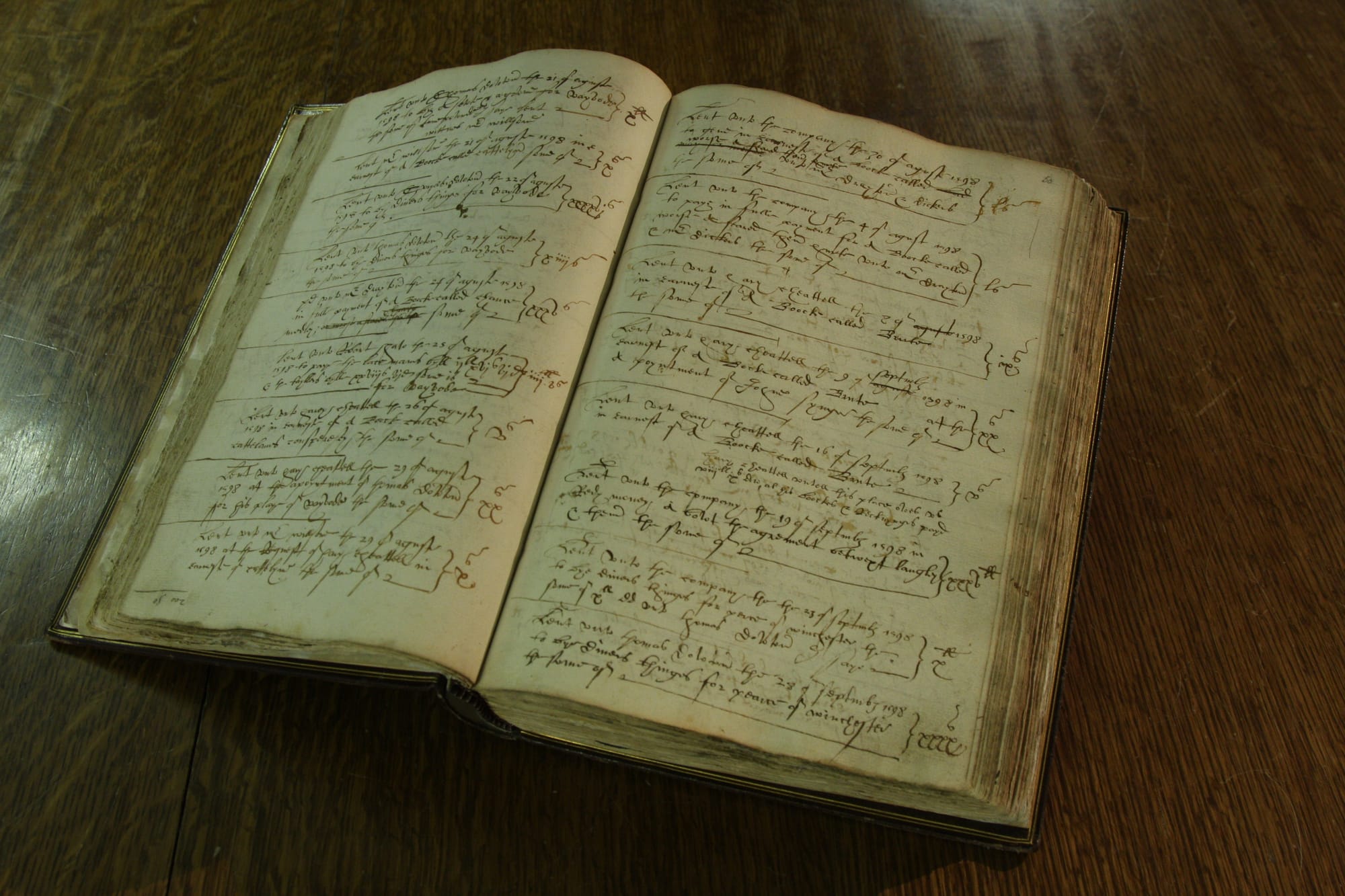

The trick, which is written in Henslowe’s sloping Shakespearean English, is hard to translate for our contemporary eyes (if you can parse out any words from the associated photo, you’re a better scholar than I am). The good news is that it was translated in the 19th century by W.W. Greg, which is marginally (emphasis on marginally) easier to decipher.

The trick involves 13 playing cards laid out in a circle, with a spectator selecting a number from one to 12 at random and then moving a certain number of spaces clockwise and then counterclockwise, ultimately ending up on the number they originally selected.

The problem, however, was that the trick as described by Greg didn’t work. Historian Rob Eastaway, however, sent the write-up to mathematician Colin Beveridge, who, in an Aperiodical blog post, describes Greg’s description as “a game of Telephone that started centuries before the telephone was invented.”

Beveridge came up with a version of the trick that works, however, with the help of his 10-year-old son. It involves modular arithmetic. (You can Google that, or even better, watch a video of Beveridge and his son demonstrating the trick.)