The idea behind the Conference on Magic History, a biennial convention between 1989 and 2015, was always to celebrate the history of our art by putting it onstage. Sometimes “onstage” meant that the magic might be displayed, discussed, or analyzed. And sometimes “onstage” meant that long-forgotten deceptions were being dusted off and performed once again. They were more than just tricks. They were a chance to feel Robert-Houdin, Kellar, Maskelyne, or Thurston at work once again, effectively rolling up their sleeves and engaging in the work that had made them famous.

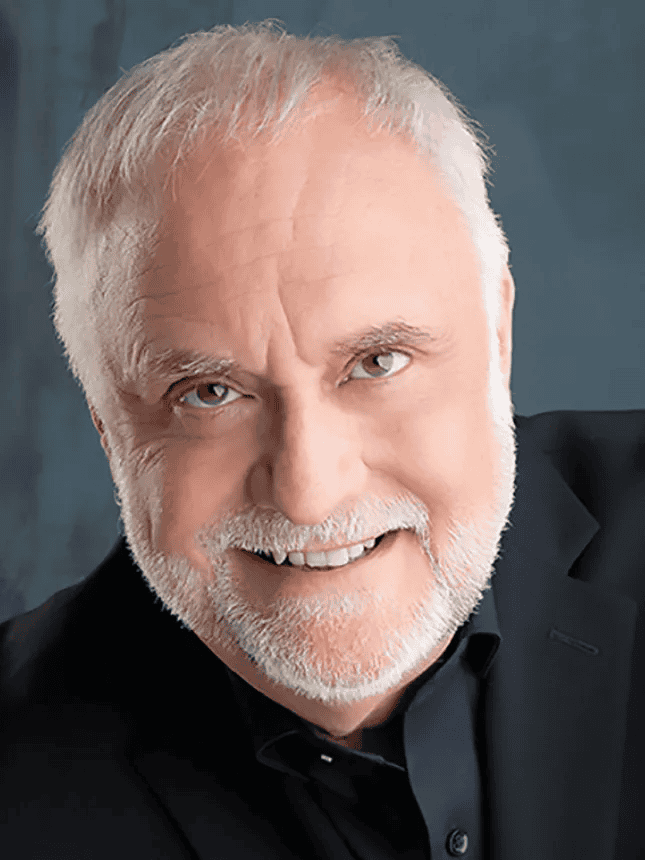

But those recreations were difficult operations, and we each had our own interpretations of how they should be balanced for a modern audience of magicians. Should we explain the secrets? Should the technology become the show? John Gaughan’s interest was invariably the apparatus itself: the particular combination of principles or machinery that made some magic wonderfully deceptive. At our first conference in 1989, he proudly displayed his accurate recreation of the famous 1769 von Kempelen chess automaton, the infamous Turk.

John showed the apparatus. An odd, man-sized automaton was seated behind a wooden chest. Three large doors in the front of the chest were opened. The interior was empty except for an array of gears and levers. The mechanical man was shown empty; no one was hidden inside the automaton. John then invited someone from the audience to play a chess game opposite the Turk. The Turk moved its hand precisely, understanding the game and moving each piece in the proper manner. At the end of the demonstration—after the Turk quickly won—John promised to show the attendees how it was done. Our audience, seated in the hotel ballroom, craned forward to see what part of the secret they had missed. John lifted the top off the chest and his concealed assistant, smiling and sweating, stood up. There was a momentary pause, and then a low groan of disappointment, as if all of the air had been pulled from the room.