In 1997, Juliana Chen won first place in the manipulation category at FISM. She was the first woman and the first Chinese magician to win gold with a solo act. These are the facts that most people already know about her. But there’s more to Juliana than that win.

It’s true that Juliana’s ground-breaking achievement nearly 30 years ago springboarded her globe-trotting career. But the story of how she got there—and what she’s done since—traces the evolution of an artist in a rapidly changing world.

Juliana was 9 years old when the Hunan Academy for Performing Arts plucked her out of school in 1972. “Every two years, they went to the normal schools all around China,” Juliana told me. “If the kids were beautiful, they talked to the teacher about them. They measured your arms, your legs. They asked what you could do—dance, sing... I did it all, but I wanted to be a dancer.”

After five audition rounds, Juliana was selected to train as a ballerina. In the five years she lived at the Academy, the demanding daily schedule started with stretching at 5:30 in the morning followed by ballet class at 9. After a lunch break, they spent the afternoon studying theatrical performance, emphasizing posture, movement, musicality, and facial expression. From 7:30 to 10 every evening, they took regular academic classes.

This rigorous program aimed to create perfect performers who could conform to established standards set by the government; at the time, arts programs across China were controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. When Juliana officially joined the Hunan Ballet Company in 1977, she had conflicting feelings about that government control. The Chinese Communist Party fed and clothed her. Her apartment was paid for. She earned a salary regardless of whether or how often she performed. But Juliana began to wonder if in exchange for having her basic needs met by the government, she was sacrificing a freedom that she had only imagined.

“Sometimes I still miss communism,” she said. “People were not very poor and not very rich, but they were kind, because you didn’t have to fight to survive.”

While Juliana spent her youth training to be a professional performer, the global stage was shifting dramatically. In 1972, the same year Juliana entered the Academy, Richard Nixon became the first sitting U.S. president to travel to the People’s Republic of China. The historic visit marked a critical step toward the establishment of full diplomatic relations between the two countries. As part of that normalization effort, the Shengyang Acrobatic Troupe toured the U.S. later that same year. The tour was a success—demand for Chinese-style circus performances increased immediately—but the Chinese Communist Party had put the cart before the horse. While Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution had been funneling investment into opera, ballet, and folk dance, China’s once-robust acrobatics program had withered.

“Chairman Mao’s wife didn’t like the circus because it was normally for very poor people,” Juliana said. Although China boasts thousands of years of acrobatic history, the circus’s modern status as cheap entertainment for the lower classes led to decades of neglect. “This was a golden time for the Chinese circus, but they had no students. So they picked from opera and dance and moved us to the circus program.”

Juliana was traded from the Hunan Ballet Company to the Hunan Acrobatic Association. Overnight, she became a foot juggler. But barely five years later, major knee injuries knocked her out of commission. While she was recovering from surgery in the hospital, a magic show aired on China’s one television station. “I saw a very good-looking Asian gentleman with beautiful movement and really good technique,” Juliana said. It was Shimada, who years later would befriend Juliana and take her under his wing as a protégée. “I thought, ‘Well, that’s very nice! Maybe I can be a magician!’”

Although Juliana returned to foot juggling post-op, her knee was still prohibitively painful and swollen. Every day, she visited the company doctor to extract fluids from the joint. She knew it was time to make a change, and the image of Shimada loomed large in Juliana’s mind. But she also knew that there was no guarantee that the Hunan Acrobatic Association leadership would allow her to make yet another transition.

Knowing her boss might turn her down if she asked for permission, Juliana decided to become undeniable on her own. There were no magic shops in China at the time, and secrets and techniques were regulated by the government. So Juliana taught herself everything she could by reverse engineering what she saw.

The Hunan Acrobatic Association already had a manipulation act named Cheng Li, and Juliana watched from the wings whenever she performed. She studied Cheng Li’s movement style to glean the magic moves. Once, she even stole a prop manipulation flower to secretly study how it was made; “Then I put it back after, because she counted everything after every show.”

Juliana practiced magic behind closed doors for a year, squeezing in sessions after full workdays with the circus company. Cards were cheap and easy to find, and Juliana made billiard ball shells out of ping pong balls. She stumbled upon her own methods through practice and experimentation.

When Juliana finally showed her boss at the Acrobatic Association what she could do, he was convinced. She quickly earned her certification, essentially a license to perform magic professionally in Hunan.

Juliana started performing immediately, but she soon started to feel like a big fish in a small pond. People she trusted told her she was too good for Hunan, but her license was limited to the one art in that specific geographical region. At the time, performers couldn’t just move to a new city or even request a transfer. “Now it’s different. Now you can go anywhere you want,” Juliana said. “I was the first one in China to jump from Hunan to Guangzhou. But not directly.”

Guangzhou had a much more famous magic program than the one in Hunan, and the city’s proximity to Hong Kong meant greater access to the rest of the world. So Juliana hatched a plan to quit the troupe in Hunan, give up her license, and take a factory job in Guangzhou, then a burgeoning manufacturing city. She had found a loophole; although everything was tightly regulated and carefully managed, the Chinese acrobatic associations weren’t coercive. When Juliana told her bosses in Hunan that she wanted to leave to pursue another career, they released her from her contract.

A few months later, she approached the Guangzhou Acrobatic Association, not as a performer from Hunan but as an independent citizen. This meant that no one could be accused of poaching talent from another province’s program. It worked; Juliana got a new license and started performing magic in Guangzhou.

As she had hoped, joining the new company also gave her the opportunity to perform outside of China. Of the troupe’s 200 total members, a cohort of only about 30 traveled abroad. As they toured, Juliana received attention from international admirers, including Alberto, a Spanish producer with whom a romance blossomed.

Alberto lavished Juliana with gifts and sent flowers to her hotel rooms. She received two letters professing his love for her, one more than 60 pages long. It was more than she could hide, and any association with Westerners was forbidden for performers. Worried she would defect, the Guangzhou Acrobatic Troupe placed Juliana under 24-hour surveillance.

Upon returning to China, Juliana was demoted from the touring team and placed in a more stationary group in the Guangzhou countryside. The government monitored her correspondence from then on, withholding letters that she and Alberto sent but never received.

Juliana wasn’t particularly interested in defecting, but she was simultaneously lovesick and endlessly ambitious. She began dreaming of ways to begin a new life elsewhere. Two goals obsessed her: to pursue love without the interference of the Chinese government, and to be recognized as a great magician—not just in China, but throughout the world. She would accomplish one of the two.

When she was still traveling with the Guangzhou Acrobatic Troupe, Juliana learned that performers were not entitled to keep their own travel documents. Her boss would hand out performers’ passports one at a time as they approached immigration, pass through himself first, and then wait on the other side to collect their documents as they exited the checkpoint. That changed in 1988, when Juliana traveled on her own to enroll in an intensive English-language program in Canada.

“When I flew to Vancouver, it was the first time in my life I held my own passport,” she said. “I was crying. When I was sitting there on the plane, looking outside, I told myself, ‘Look how high I can fly.’ Even today when I think about it I still cry, because you never felt free in China.”

In 1989, Juliana learned of the Tiananmen Square massacre while she was on the way back to Vancouver from performing for the Thai royal family. When she landed in Canada, the immigration officer informed her this was her best chance at citizenship—the Canadian government was welcoming Chinese student applications.

Juliana checked with her boss, because she was still technically an employee of the Guangzhou Acrobatic Association. He told her: “You’re on your own. It’s your choice.” She became a Canadian citizen that same year, effectively realizing her dream to begin a new life beyond China’s borders while still maintaining a positive relationship with her motherland and avoiding the mark of defection.

Suddenly, Juliana was a full resident in a place she barely knew. To ease her transition, she took a job at a furniture store while she got the lay of the land. Later, she started a graphics business that, among other things, had her typesetting Chinese-language TV guides. Eventually, a reporter for a local Chinese newspaper recognized her—before she left China, Juliana was already a star.

When his full-page story led to a gig at the Chinese Cultural Center, Juliana realized she didn’t have what she needed to do a full show; she had arrived in Vancouver with some cards and a sub-trunk that customs broke while inspecting the lid. She found her way to the local magic shop, Ken’s Illusionarium, and she was stunned; she’d never seen anything like it before. Owner Ken Gerbrandt noticed her excitement and eventually invited her to perform at the Vancouver Magic Circle’s annual Christmas event.

Shawn Farquhar, who was hosting the show that night, suggested Juliana perform second to last, right before he closed the show. But when she shot cards all the way to the back of the hall and ended with giant card fans she tossed into the air, Shawn says he “came out and said, ‘That’s the end of the show, thank you!’ Because you don’t follow that, right?”

Shawn helped Juliana get her bearings in those early days, when she was still new in Vancouver and spoke very little English. The pair became fast friends and close collaborators. Later, Juliana was the one to book Shawn in his first show in China, where he performed his bird act at a 60,000-person arena in Shanghai. The two are still close: “Shawn is like a big brother to me,” Juliana said.

That initial Vancouver Magic Circle performance is a good example of how Juliana has often taken her fellow magicians by surprise. “I did three minutes, and I think I had a 10-minute standing ovation,” Juliana said. “They told me people are always sleeping during the show, but I woke everyone up.”

Her star rose quickly from there. After she wowed at PCAM in 1992, Pete Biro offered Juliana $1,500 to perform at the IBM convention. It was a lot of money, but she asked to compete instead. He warned her the competition would be tough: Greg Frewin, Jason Byrne, and George Honda were already on the roster. Juliana remembers telling Peter: “I don’t know them, but I know myself. I want to do the competition.” She won.

Then Ton Onosaka invited Juliana to Japan to appear on the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation’s 1993 Stars of Magic special. While she was still backstage doing her makeup, she heard her music playing on set. She rushed downstairs to let them know she wasn’t ready, only to find out it wasn’t her music at all. Victor Voitko was using the same track, Enigma, and his act was on first.

Influenced by Chinese beauty ideals at the time (which prioritized white features),

Juliana had cultivated what she calls a Western aesthetic. But after the music snafu in Japan, she decided to honor her heritage instead: “I looked at myself and said, ‘It doesn’t matter how sexy you look, you’re still Chinese.’ That’s when I started building an act to mix in my Chinese culture.”

Bian lian, or the art of face changing, falls under the purview of traditional Chinese opera. The refined and highly detailed masks express character and emotion, and the method of magically swapping masks is a closely guarded secret.

Juliana decided to make traditional bian lian the anchor of her Chinese-inspired magic act, adding a few touches of her own, like establishing the mask as her true face by revealing only black fabric behind it, and floating the mask in the middle of the stage before beginning the series of changes.

Juliana’s new act also included many of the card manipulation techniques she had largely taught herself. Over time, she refined her own method of shooting cards using the strength of her fingers instead of throwing them with a snap of the wrist (or with the help of a rubberized thumb tip).

But when she debuted her new act as an invited guest performer at FISM 1994 in Yokohama, she felt the audience’s energy waning. When she got home, she studied the tape; to this day, Juliana often tells magicians that video is the best coach. She realized that while her first few face changes got great reactions, more changes meant diminishing returns.

“The culture around the face change is that the more times you do it, the better you are. They do it 10 times, but the effect is the same. It’s repetition.”

So she adapted. She cut out half of the changes and redesigned the masks to make each one pop; instead of traditional bian lian masks, which are highly detailed but difficult to distinguish from a distance, she used full-color green, red, and orange masks that glowed under blacklight.

She swapped her lush red-lined cape for an all-black version that wouldn’t draw attention away from her face and lined the edges and seams in UV-reflective neon.

In 1996, Juliana took second place with the new act at the Magic Hands Fachkongresse in Dresden. Then she won the Grand Prix at the 21st Congreso Nacional De Magia in Vitoria-Gasteiz. Juliana remembers Ton Onasaka approaching her after that, saying: “Let’s do a real competition. Let’s go to FISM.”

Ton-san made Juliana a compilation tape of 50 manipulation acts from between the 1930s and 1950s. She canceled all her performance contracts in the year leading up to FISM. “I practiced every day, 40 to 50 times a day,” she said. “Load it, practice, load it, practice.” Each time, she reset nearly 700 cards. Her first steal was a stack of 90 cards.

We all know what happened next. Juliana took first prize in the manipulation category at FISM in Dresden in 1997—Ivan Necheporenko won the Grand Prix. Looking back, Juliana sees the outcome as a stroke of luck: “If I won the Grand Prix, maybe people would say, ‘Oh, she’s not that good.’ Because I lost, people say, ‘Oh, she’s so good, she should have won.’”

After FISM, Juliana was everywhere. She lined up years worth of back-to-back contracts at independent theaters across Germany and eventually throughout Europe. Mainstream publications celebrated her achievement and she was featured on major TV networks around the world. In the late ‘90s, she appeared on World’s Greatest Magic V, Champions of Magic 3, and at Caesars Magical Empire. Juliana was flying back and forth to Las Vegas so often that she had already gotten a green card, and by 2000, she decided to move there permanently. Although she made Canada and then the United States her home, Juliana has long been dedicated to bridging the magic communities in North America and China.

In 1993, she collaborated with the Chinese Magic Acrobatic Association to start IBM Ring 311 in Guangzhou. Since 1994, she has been producing the Shanghai Magic Festival, which is attended by 2,000 Chinese magicians every year. At the SAM convention in Las Vegas in January 2020, Juliana produced a first-of-its-kind gala show called The Gold Medal Winners of China.

In many ways, this cultural bridge is built atop the exacting standards Juliana has become known for. As an official FISM judge since 2015, Juliana has been committed to sharing her opinion honestly and ignoring the politics that plague magicians everywhere. “When the young magicians ask me what I think, I just tell my truth,” Juliana said. “Which one is good? Which one is bad? So they respect me.”

Sometimes, she leaves it at that: good or bad. But when she’s asked, it’s easy for Juliana to recommend specific improvements. She is constantly, reflexively inventing solutions that could make an act stronger and more magical.

While she believes some FISM judges—and most magicians—prioritize certain aspects of magic over others, Juliana is holding out for the whole package: a balance of presentation, creativity, and technique. While she sees technical skill as table stakes and feels innovation is important, they’re nothing if an act doesn’t inspire feeling. “Magic is not just tricks,” Juliana said. “It’s an art.”

Juliana holds the magicians she mentors to the same sky-high standards. In 2009, she met 16-year-old Yang Yang, her first mentee, at the Shanghai Magic Festival. The young magician from Tianjin became so successful in China (and so regularly mobbed by fans) that the Acrobatic Association funded a national tour of the one-man show Juliana wrote for him.

Juliana’s students: Yang Yang (left) and Layla (right)

These days she is mentoring Layla, a 15-year-old manipulator who garnered attention and praise when she represented the U.S. at FISM in Torino.

Then there is Ding Yang. When Ding Yang approached Juliana, she had already won magic competitions in China with her bird act, but she dreamed of competing at FISM. When Juliana agreed to help, Ding Yang left behind her husband and 3-year-old son to travel to Canada and begin training for FISM 2022 in Quebec City.

Juliana spent months helping Ding Yang prepare, starting by introducing her to Greg Frewin. Juliana thought Greg was a perfect fit not just because of his past FISM win (first place in General Magic at Yokohama), but because she felt his modern style would help Ding Yang evolve her performance for a broader audience. “The three of us were a good team,” Juliana said.

With Greg Frewin in his workshop; working with Ding Yang on her groundbreaking bird act

While Juliana feels Ding Yang deserved to win—she took second prize in General Magic—she still wells up with pride when she reflects on all Ding Yang has accomplished. “Every day when I got up at 6, she was already standing on the platform fully loaded,” Juliana remembers. “She is a professional. She grew up with this idea of practice, practice, practice.”

The parallels are clear; Ding Yang was trained in a contemporary version of the same government-sponsored arts program that raised Juliana. She got her start in the acrobatic program as a contortionist and hand balancer, then transitioned to magic after an injury. Across generations, a shared experience of rigor, commitment, and sacrifice connects Juliana and her student as magicians, artists, and athletes.

Although Juliana sometimes talks about approaching the end of her performing career, she shows no signs of slowing down. She recently debuted a new parlor act, and she’s been working on her own close-up set. When she does stop performing, she plans to go all in on directing and producing magic, which she has already been doing for decades. But Juliana is a perfectionist. After all she’s done, she still doesn’t feel successful enough. She’s not sure she ever made it to the top.

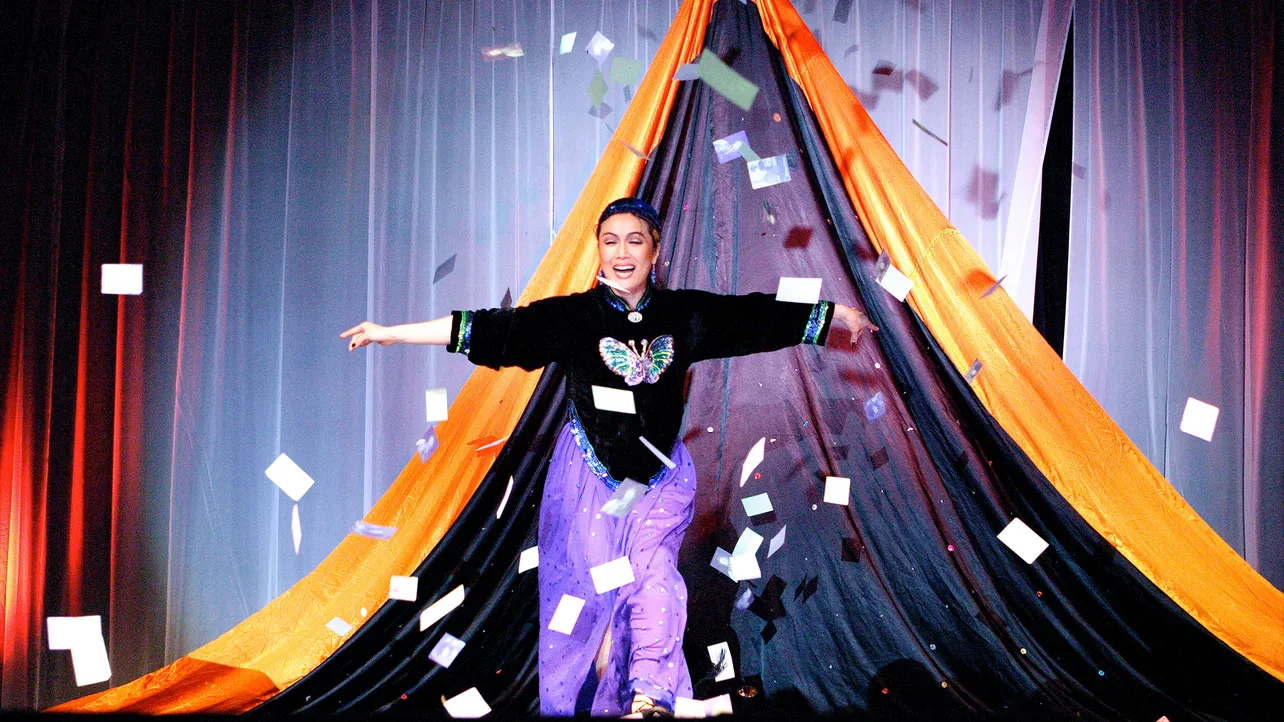

Juliana still performs her FISM-winning act from time to time. She floats as she moves across the stage, each movement a delicate step in a highly choreographed dance. Every production proves her long-standing criticisms that modern manipulation is too harsh. Juliana oozes ease, projecting effortlessness with every sinew.

Mystify Magic Festival founder Leah Orleans said Juliana was long at the top of her performer wishlist: “The quality of any show is immediately going to go up if Juliana Chen is in it.” To me, seeing Juliana open Mystify’s first gala show felt simultaneously like a nod to her historical achievement and a refusal to forget decades of hard work by women who haven’t always gotten their due.

Since Lausanne in 1948, there have been a total of 29 FISM competitions to date. Of note, two conventions in the 1950s awarded prizes in a category called “Female.” Other than that surely well-intentioned anomaly, only two solo female acts have ever topped their categories at FISM. This is not the place to speculate about why, or about whether or not increased representation will fuel change. In 2025, Léa Kyle became the second woman to do it when she took first place in General Magic in Torino.

But the first will always be Juliana Chen.

Photos courtesy of Juliana Chen