GAËTAN BLOOM: I met Jean Merlin in 1965, when I was just 12 years old. Dominique Webb had opened a magic boutique in Paris, and a school for young people and adults. Jean Merlin had been hired as head teacher. He was 21. Over the next few years, Jean taught me the best versions of the classics, from Dai Vernon’s Linking Rings, to Slydini’s Paper Balls, to Goshman’s sense of timing.

In 1973, Jean went on a U.S. lecture tour of and he returned with stories about The Magic Castle. Jean was a very good pianist, and spent hours with “the soul” of Irma, the invisible pianist, playing songs and discussing Jean’s hero, Thelonious Monk. At The Castle, he also discovered a recipe that became a favorite: eggs Benedict.

He loved cooking, and could have been a chef. Invited to his home, you were given a menu, specially printed, just for you; this was a family tradition. His kitchen housed a thousand surprises. Once, I saw five toasters on a counter, standing in a line. “Jean? Why five toasters?” “Bloom (he always called me Bloom), if there are 10 of you at the table, and you all want hot toast, you need five toasters!”

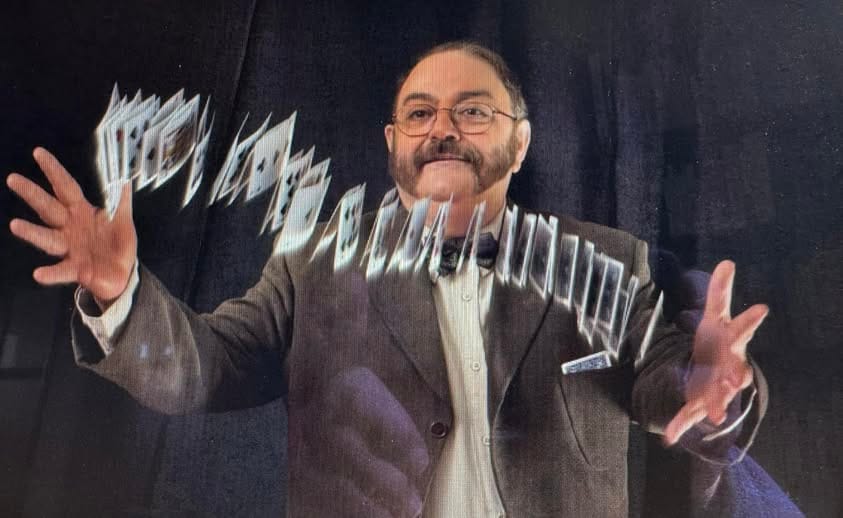

JEAN-JACQUES SANVERT: Knowing him was knowing the very best things in life. He could do magic for all kinds of audiences, including children. He starred in cabarets at a time when they were so numerous in Paris.

I remember when he launched Mad Magic magazine in 1975. He produced it with his friend James Hodges, who made the drawings. It was superb. Jean’s balloon book became a bestseller, and of course his Jean Merlin Book of Magic (three volumes) became an instant collector’s item in France. He was a pioneer in rope magic (he gave lessons to Francis Tabary), and also in balloon modeling.

BLOOM: Jean described all his rope routines with just numbers and drawings—without text—making it international. Mad Magic is very difficult to translate, because it uses his own turns of phrase, a sort of slang. You see that in The Jean Merlin Book of Magic, too. He is very incisive and funny, a little like Steve Spill’s writing.

Jean knew he was sick about 10 years ago with pulmonary fibrosis, but he didn’t say it. He wanted to work as long as possible. Last July he called me, canceling one of his famous big meals, and said that he didn’t want people to see him “like that.” I said, “It’s us! It’s different! I want to see you, and I’ll make the meal.” So I came around and found him with his partner, Patricia. He was very thin, and short of breath, but everything was there—the voice and the gesture. He enjoyed the meal. And so, a group of his friends organized culinary surprises for him, which he appreciated. They planned their visits with the help of his children, Marc, Patrick, and Patricia.

Jean died on April 4, in his 80th year. I saw him 48 hours before the end. He was very tired, but smiled at me with his eyes. We shook hands very tightly. We said vous (“you!”) to each other until the very end.

SANVERT: He was one the most outstanding magicians in France—but he was above all a perfect gentleman. For me, his best creation was The Card Trick That Can’t be Done. The effect? Well, he tries to have a card chosen, but the card can’t be chosen. It’s 20 minutes of nothing, with the audience laughing hysterically. After his failures, he ended with the line, “A lot of magicians would now find your card! Not me!” That was Jean Merlin.

BLOOM: For his burial, he didn’t want a mass, but asked for a broken wand ceremony. So I conducted it—my way. After the wand was broken, I put the two pieces back into the case—and then, pulling on the end of the wand, it emerged, restored again. I put it on the coffin. I like to think that Jean would have been very pleased.

Thank you my dear, Jean—my friend, my master.

Photos courtesy of Marc Merlin