We’re told that Paul Delaroche, a popular 19th-century French painter, encountered his first daguerreotype—a print using the earliest process for photography—and reacted with horror: “From this day, painting is dead.” It’s a reminder that painting was sometimes thought to be utilitarian— simply to show us what things look like, and that photography must have shocked viewers by accomplishing that easily, with technology.

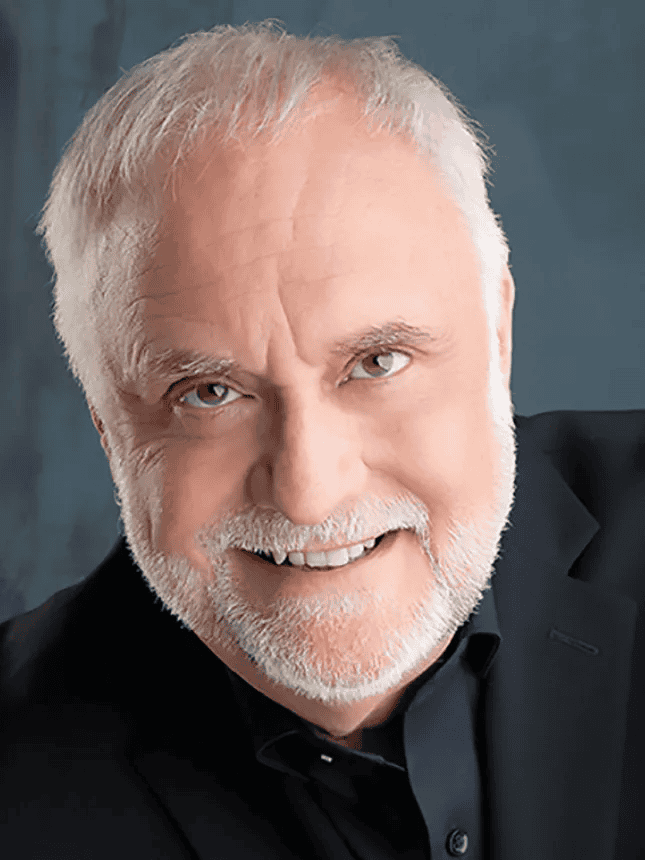

In the August issue of Genii, the artist, photographer, and magician Zakary Belamy reminds us that, yes, photos can be very handy for a driver’s license, but some photographers have set their aspirations higher, offering special, subtle insight into a person’s personality and achievements.

Belamy’s Studio Noir project—elegant and engaging black-and-white portraits of magicians—proves the point. Noah Levine interviewed him, and Belamy offered some of his amazing work, a backstage view of the process, and the source of his inspiration. Take a look at “Studio Noir, Behind the Lens With Zakary Belamy.”

My friend Kevin Spencer is the subject of our second feature. Kevin and Cindy Spencer toured performing arts centers with their popular illusion show for many years, and when Kevin retired from those performances, he found another challenge—using magic as both therapy and inspiration for kids and adults with disabilities. If you’re lucky enough to know him, you’ve heard his excitement for this work, and his pride for its impact. Vanessa Armstrong interviewed him, and some of his associates, for her feature, “Can You Teach Me That?” Yes, they’re tricks to most of us, but it’s a reminder that we are, indeed, working with potential magic—very powerful magic.

And then, turn the page to Paul Heller’s concise chapter on Americana, the celebrated career of Ben Butler, an especially clever pig who—with his owner—indulged in a bit of conjuring or trickery. It’s a great story that hasn’t been told before, and it may remind you of the colorful characters and oddities in Ricky Jay’s book, Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women. Just turn to “Charlie Winn’s Educated Pig.”

When it comes to performing pigs, I recall one of Ricky’s favorite stories, which he told masterfully and enshrined in the pages of the above book. It happened to Fred Leslie, who trained pigs for Lehman Brothers Circus around the start of the 20th century. At that time, there was a fondness for pig acts, where the animals marched around in a line, danced atop round stands, climbed ladders, and played on seesaws. Pigs are smart and make very enthusiastic performers. The problem is that they grow quickly. The cute little pigs learn their tricks, but then they grow to enormous proportions. Leslie was constantly buying young pigs, teaching them, and then swapping out one cast for another so his stars were small and attractive.

During a tour, the circus pitched its tent next to an actual pig farm, so the trainer took advantage of the situation. He asked the farmer if he wanted to buy his group of adult pigs. The farmer agreed and that afternoon the pig performers were retired behind the fence of the adjoining farm. We’d say they had earned their retirement, except that the pigs were probably destined for bacon.

That evening, when Leslie’s circus act started, the adult pigs heard their music and became agitated. They climbed over the fence and ran into the circus lot—evidently concerned that they were missing their cue. They nosed their way under the tent and then dashed into the ring. The audience was shocked to see a drove of enormous, angry pigs invade the tent, run up to the young pigs, and shove them away from the equipment. Then the giant pigs proudly took over, commandeering the spotlight as they danced through the various maneuvers of their well-rehearsed act.

You see, you thought that was going to be a story about pigs, but it’s actually a story about performers.

Speaking of unexpected performances, for some mysterious reason the pages of the August magazine offer—among many other things—a passing obsession with spring snakes in a can. Please take a look at these Genii here and here. You might want to ask the editor how this happens, so I’ll sidestep that question by confessing I have no explanation. I merely report.

We keep hearing from people who are enjoying the new Genii, and I get reports that the issues seem to linger through the month—something that can be picked up again and again from the coffee table. I hope that’s the case. Recently Murphy’s Magic—the omnipresent wholesaler—decided to stop wholesaling Genii to magic shops. Perhaps there’s not enough profit in it for their system. No hard feelings, but we are obliged to explain to magic shop habitués why they can no longer buy Genii off the “newsstand,” so to speak. It’s another example of the changing business models, and we see that some shops are arranging wholesale magazines directly from our office.

We do our very best to support magic manufacturers and dealers. And as you’ve probably noticed, we regularly carve out space to introduce you to brick-and-mortar shops that have earned the trust of magicians. This month it’s Joe Pon’s Misdirections in San Francisco. You might also peruse Ben Winn’s interview with Teller about the long lost magic shops of Philadelphia.

Oh yes, we all get a tear in our eye contemplating those wonderful stores, but do we actually support them? Winn and Teller point out how accessibility to online products can be attractive, but is not always an advantage. I’ve noticed a lot of discussion about modern tricks that are intended to be seconds long. Magicians seem to think this is a result of the shorter attention span of audiences. Joe Pon explains that these are tricks not intended for actual people, but to amass online hits. Once that becomes the trend, other magicians imitate that style. (This suggests the problem is the shorter attention span of magicians.)

If you choose to talk about literature, there’s a vast difference between novels and fortune cookies. When I was growing up in magic, we stood around the magic shop and talked about the “literature” of magic—if you’ll excuse the grand analogy. The process is much tougher if you’re limited to analyzing the stylistic prose of fortune cookies.

I would grumble that the internet has the ability to sell us some awful products, and then discourage us from talking to human beings about them.

One more point. Dealers continue to define our art. They tell us what to buy, they establish the trends, they create the categories, and then the products. (We might be shocked to consider how much Robert-Houdin—yes, even Robert-Houdin—was in the pocket of the French magic dealers, influenced by their products.)

I remember Sid Lorraine’s assessment of Percy Abbott’s skill at demonstrating and selling some perfectly awful tricks with wonderful panache. But when those dealers leaned across the counter, they were speaking to us and listening to us. The online dealers must “lean across the counter” and sell to tens of thousands at a time.

You should make a habit of going to magic shops whenever you can. It’s not about nostalgia. You’ll hear different points of view and breathe a different quality of air.

Speaking of crowds of magicians, it’s convention season; we’ll have reports starting in September. If you get a chance, say hello to the Genii team at MAGIC Live. Take a look at the latest magazines, and let us know how we’re doing.